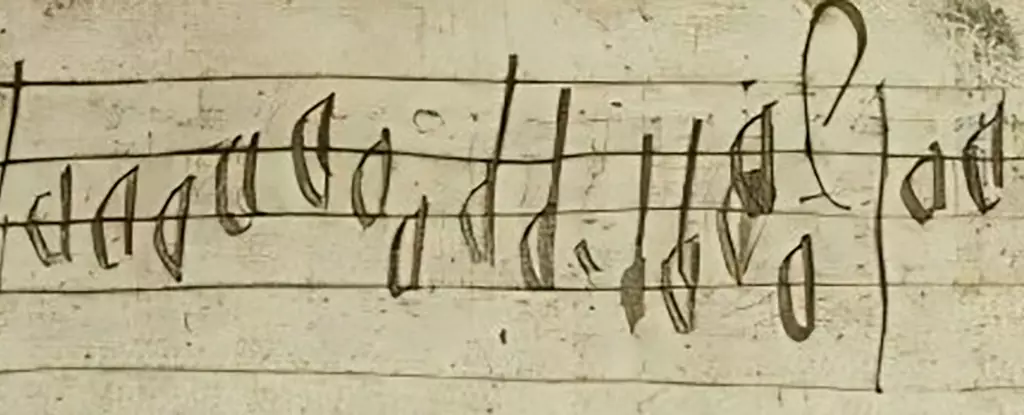

Music possesses an extraordinary ability to evoke memories and transport listeners through time and space, often conjuring vivid images of places and experiences long since past. A recent study has reshaped our understanding of Scotland’s musical landscape by bringing to light a 55-note fragment from the 16th century. This tiny piece of notation, discovered in the margins of a historically significant text known as the Aberdeen Breviary, opens a window to a cultural soundscape that had previously been lost to history. The Aberdeen Breviary, printed in 1510, is notable not only for its religious content—comprised of prayers, readings, and hymns—but also as the first complete book produced in Scotland via the printing press.

In 2011, a team from KU Leuven and the University of Edinburgh stumbled upon this fragment, which has since been analyzed for its historical and musical potential. Researchers have linked this fragment to a lesser-known Christian chant, known as “Cultor Dei, memento” or “Servant of God, remember,” that continues to see use in certain Anglican congregations during the Lent season. However, uncertainty looms over whether the fragment was initially intended for vocal harmony or instrumental arrangement. Regardless, this discovery offers essential insight into Scotland’s liturgical music practices prior to the Reformation.

Musicologist David Coney succinctly encapsulates the significance of this fragment, stating that it allows us to hear a hymn that lay dormant for nearly five centuries, thus enriching our understanding of Scotland’s musical traditions. The fragment, although devoid of a title or composer attribution, has been identified as a polyphonic piece, indicating that multiple melodies were sung or played concurrently—a hallmark of sophisticated musical composition.

One of the key aspects of this newly uncovered music is its alignment with the tenor part of a vocal piece that harmonizes the existing melody of “Cultor Dei, memento.” This connection not only breathes life into a previously silent notation but also offers a roadmap for reconstructing the remaining parts of the piece. The researchers have taken strides to recreate a version of the hymn, giving modern ears a glimpse of what it may have sounded like centuries ago. Listening to this reconstruction can evoke profound appreciation for the artistry and complexity of pre-Reformation sacred music.

James Cook, another musicologist on the project, challenges the long-held notion that Scotland was devoid of rich sacred music before the Reformation’s upheaval. This new evidence suggests a thriving musical culture in Scotland’s religious institutions, akin to the robust musical traditions that flourished elsewhere in Europe during the same period. The study reveals that despite the Reformation’s efforts to erase much of the historical record, the thread of high-quality music-making remained woven throughout Scotland’s ecclesiastical structures.

The implications of this discovery extend beyond just this single musical fragment. The researchers have delved into the book’s origins and ownership history, establishing links to notable locations such as Aberdeen Cathedral and St Mary’s Chapel in Rattray. However, the mystery of the piece’s author remains unsolved, offering tantalizing hints about the untold stories of musicians and composers from that era. The project has inspired scholars to search for additional musical notations inscribed in the margins of other 16th-century printed texts, indicating the possibility of unearthing further artifacts from Scotland’s musical heritage.

As Paul Newton-Jackson notes, this discovery may well encourage renewed investigations into Scotland’s libraries and archives, where more historical anomalies are waiting to be revealed. Each fragment of music carries with it the whispers of lives lived, moments cherished, and spiritual experiences expressed.

The unveiling of this fragment is not merely a scholarly triumph; it signifies the profound impact that music has on cultural identity and historical continuity. As we navigate our contemporary landscape, marked by rapid technological advancements and globalization, this rediscovery serves as a reminder of the importance of preserving cultural artifacts that embody our shared histories.

Ultimately, the reemergence of this 16th-century musical piece illustrates how music can connect disparate eras, bridging the gap between past and present. As historians and musicologists continue to explore the myriad ways these ancient melodies shaped the spiritual landscapes of their time, we are reminded of music’s indelible role in the human experience—an eternal testament to our desires, beliefs, and communal identity. The journey through time continues, one note at a time.

Leave a Reply