Recent studies have unveiled a troubling trend amongst astronauts spending prolonged durations aboard the International Space Station (ISS): significant shifts in vision. Research indicates that an alarming 70% of astronauts who endure spaceflights lasting between six to twelve months demonstrate varying degrees of visual impairment. This phenomenon, termed spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS), raises critical questions regarding the implications for future deep-space missions, particularly as humanity sets its sights on destinations like Mars.

Astronauts affected by SANS exhibit a spectrum of symptoms including swelling of the optic nerve, alterations in the shape of the eyeball, and diminished sight. These ocular disturbances are primarily attributed to the body’s struggle with fluid redistribution during periods of microgravity. The fluid shifts increase pressure on ocular structures, leading to complications that range from mild discomfort to severe vision deterioration. While many astronauts recover upon returning to Earth’s gravity, the lingering effects and long-term consequences of SANS remain poorly understood, especially for those who may embark on missions that extend beyond the confines of low Earth orbit.

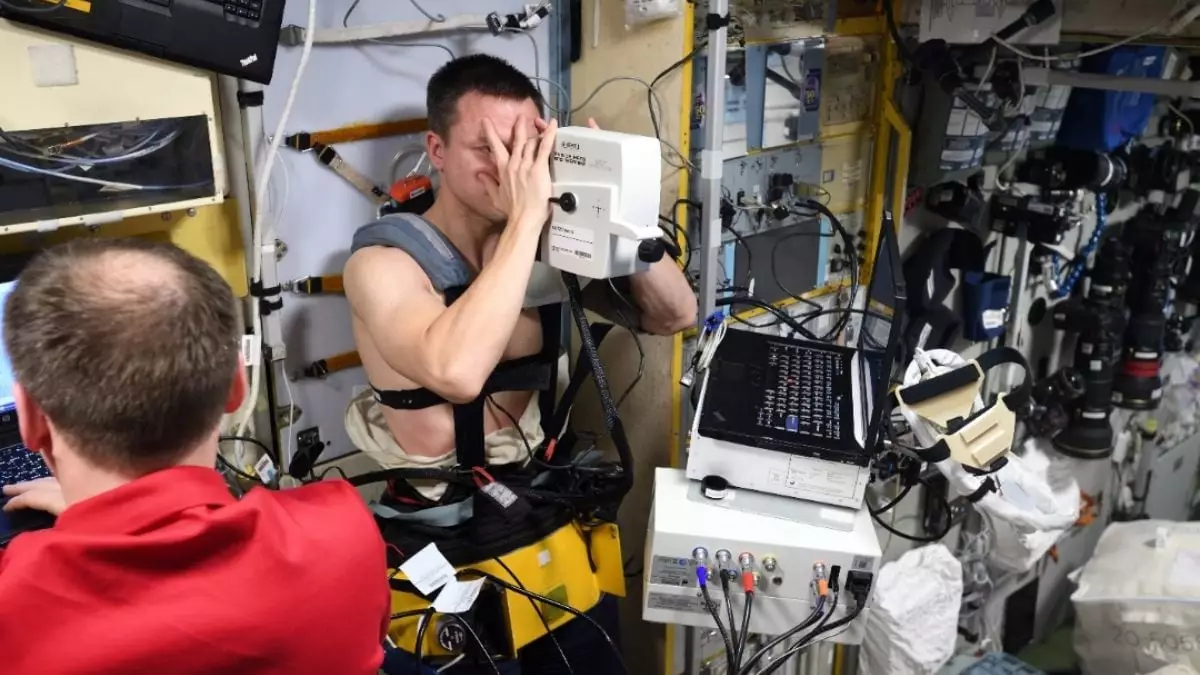

An insightful study led by Santiago Costantino at the Université de Montréal provided concrete data on the extent of these ocular changes. The research, which involved 13 astronauts from various nations with an average age of 48, meticulously tracked eye measurements before and after their missions. Key findings illustrated a 33% decrease in ocular rigidity, an 11% drop in intraocular pressure, and a substantial 25% reduction in ocular pulse amplitude. Additionally, some astronauts displayed an abnormal increase in choroidal thickness, further underscoring the scope of SANS. Understanding these changes is paramount as they not only influence the astronauts’ immediate visual capacity but could also have severe implications for their long-term health.

SANS is not a new issue; this condition has been documented since the early 2000s, with similar symptoms reported by Russian cosmonauts aboard the Mir space station. NASA officially recognized the syndrome in 2011, highlighting the need for immediate attention to astronaut health and safety in the challenging environment of space. It has become increasingly clear that microgravity poses unique risks that must be addressed through strategic planning and innovative solutions.

To combat the adverse effects of SANS, several countermeasures are currently under review, including negative pressure devices and targeted nutritional interventions. Moreover, scientists are looking to develop pharmaceutical treatments aimed at stabilizing ocular health during prolonged space travel. Identifying which astronauts are predisposed to severe ocular complications is also a focus of ongoing research. As noted by Costantino, the mechanical changes observed in the astronauts’ eyes could potentially serve as indicators, or biomarkers, for early detection of SANS, aiding in timely intervention.

The implications of SANS extend far beyond the immediate health of astronauts; they represent a formidable challenge to the future of human space exploration. As missions become longer and more ambitious, safeguarding astronaut vision is essential. Space agencies must prioritize this issue, advancing research and implementing proven strategies to protect against the risks posed by extended stays in microgravity. By addressing these concerns, we can help ensure that the dream of deep-space exploration remains a reality, paving the way for future generations to journey beyond our planet.

Leave a Reply