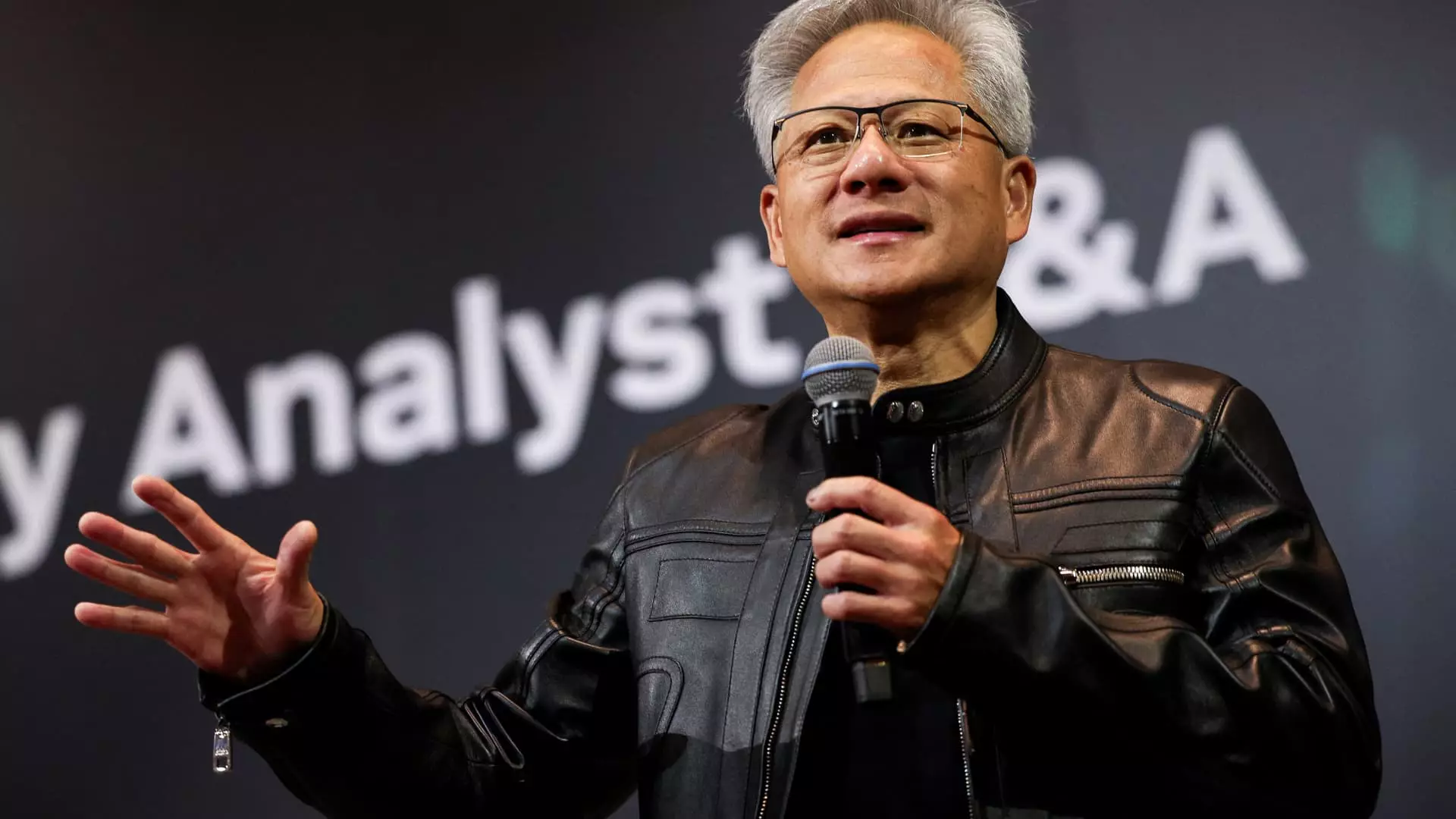

In an era where technological dominance is perceived as the pinnacle of national power, the United States is increasingly embroiled in a paradoxical pursuit: promoting its technological sovereignty while simultaneously banking on foreign giants like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC). The recent praise lavished upon TSMC by Nvidia’s CEO, Jensen Huang, underscores a troubling reality — America’s reliance on Asian semiconductor manufacturing is not only persistent but arguably foundational to its technological ambitions. Instead of fostering genuine self-reliance, federal initiatives such as the CHIPS Act reveal an awkward dance of aspiration and dependence, because the truth remains that U.S. leadership in chip design does little if it cannot secure the manufacturing backbone supplied predominantly by Taiwanese firms.

The U.S. government’s flirtation with taking equity stakes in key players like TSMC further complicates this narrative. Rather than fostering true domestic manufacturing independence, Washington might be tacitly endorsing a system where strategic vulnerabilities are masked by financial influence. By positioning itself as a major stakeholder in a Taiwanese company, the U.S. essentially perpetuates a fragile dependency under the guise of national security. This reliance on TSMC — a leader in the global semiconductor fabrication industry — raises hard questions about sovereignty and the illusion of control.

The U.S. Semiconductor Dream — An Elaborate Mirage?

The bipartisan support behind the CHIPS Act was ostensibly driven by a desire to restore U.S. leadership in chip manufacturing. Yet, the actual outcome suggests an incomplete and superficial effort. Promises of billions of dollars and the establishment of new fabrication plants in Arizona are significant, yet these are dwarfed by Taiwan’s current dominance in advanced chip manufacturing. TSMC’s remarkable $165 billion expansion plan across the U.S. and its critical role in the global supply chain underline an uncomfortable truth: the United States remains a consumer, not a producer, when it comes to cutting-edge semiconductors.

This situation becomes even more complex when considering the U.S. government’s conflicting stance. On the one hand, officials like Howard Lutnick hint at taking equity stakes in foreign firms like TSMC to accelerate domestic chip production. On the other, official reports dismiss such plans, pointing to increased U.S. investment in domestic facilities as a means to curb reliance. This ambiguity reveals a strategic crisis — how can long-term sovereignty be achieved if the core manufacturing capacity remains rooted in a geopolitically volatile region? The U.S. risks a scenario in which its technological future is secured only through a fragile web of strategic alliances with the very entities it seeks to dominate.

Strategic Vulnerability in a Globalized Supply Chain

The reverence expressed by Jensen Huang for TSMC’s achievements is more than just corporate flattery; it exposes a structural weakness embedded in the global semiconductor ecosystem. While the U.S. pushes for increased domestic investment, the reality is that advanced chip fabrication is an inherently complex, capital-intensive process that Taiwan has mastered over decades. The implication is that, despite political rhetoric, if geopolitical tensions escalate, the continuity of supply could be threatened with little warning.

This dependency becomes clearer when considering that TSMC is not just a manufacturing partner, but an integral node in the economic and strategic fabric of global communications, defense, and consumer electronics. Any disruption — whether through conflict, diplomatic fallout, or technological embargoes — would have catastrophic consequences for U.S. tech industries. The narrative that the U.S. can simply “bring manufacturing home” is overly simplistic and ignores the deeply entrenched realities of advanced semiconductor fabrication.

The Center-Right Approach to Technological Sovereignty

As a center-wing liberal, I see the current trajectory as emblematic of a broader ideological tension: the desire for strategic autonomy versus the inconvenient facts of global economic integration. While there is merit in fostering domestic manufacturing and reducing vulnerabilities, the notion that this can be achieved solely through subsidies, government stakes, and political rhetoric is optimistic at best and willfully naive at worst.

The geopolitical landscape has rendered semiconductor manufacturing a battleground — one where cooperative global supply chains are the only viable option for now. The U.S. should not fall into the trap of thinking that foreign capacity can be fully replaced or that leadership can be consolidated overnight. Instead, a nuanced approach that integrates strategic alliances, diplomatic efforts, and targeted investments is essential. Rhetoric that elevates firms like TSMC as just “very smart” investors glosses over the underlying dependency that American technological strength remains tethered to foreign manufacturing hubs.

In this delicate balancing act, American policymakers should recognize that their goal isn’t merely to boost domestic production but to elevate a resilient and diversified supply chain that reduces strategic risk. Dreaming of self-sufficiency through aggressive subsidies or government stakes without addressing the foundational global dependencies is a recipe for future disappointment. The illusion of control is precisely that: an illusion, which masks the more pressing need for pragmatic, realistic strategies rooted in a profound understanding of the interconnected global semiconductor ecosystem.

Leave a Reply