As healthcare providers continue to navigate the complexities of aging and chronic health conditions, the implications of antibiotic use on cognitive health in older adults have garnered significant interest. Recent findings, drawn from extensive longitudinal studies, have provided some clarity, yet they also highlight the nuances that must be considered in interpreting these results. A large-scale study has made strides in determining whether antibiotic prescriptions correlate with an increased risk of dementia in generally healthy older adults, but the study’s context and limitations require careful analysis.

The research, led by Dr. Andrew Chan and his team at Harvard Medical School, monitored over 13,500 participants aged 70 and older for nearly five years. The subjects participated in the ASPREE trial (ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) and its subsequent extension. The study aimed to dissect the relationship between antibiotic use and cognitive decline, particularly focusing on dementia incidence and cognitive impairment without dementia.

The findings revealed no statistically significant association between antibiotic usage and dementia risk. Specifically, the hazard ratios reported (HR 1.03 and 1.02 for dementia and cognitive impairment, respectively) suggest a neutral impact of antibiotics on cognitive function during the follow-up period. This conclusion provides a measure of reassurance to healthcare practitioners prescribing antibiotics to older adults, who often face higher incidences of infections and chronic health issues.

Despite its contributions to the existing body of knowledge, the study is not without its limitations. The primary cohort consisted of individuals who were relatively healthy at the start, with exclusions for serious disabilities or cognitive impairments. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to older adults with multiple comorbidities or cognitive deficits that are more prevalent in the population at large.

Additionally, the antibiotic usage data derived from filled prescription records may not accurately reflect actual consumption, as many individuals might not complete their prescribed courses or might use antibiotics obtained through other means. Such discrepancies can obscure the true relationship between antibiotic exposure and cognitive outcomes and point to the necessity for further research in diverse populations.

The study’s results align with previous inquiries that have yielded inconsistent findings regarding the cognitive impacts of antibiotic therapy. While some prior studies have suggested associations between antibiotic exposure and cognitive decline, such as findings from the Nurses’ Health Study II, the conclusions of those studies have not uniformly been confirmed. For instance, the reported long-term cognitive effects noticed in midlife women following substantial antibiotic use starkly contrast with Chan’s findings in a predominantly healthy elderly cohort.

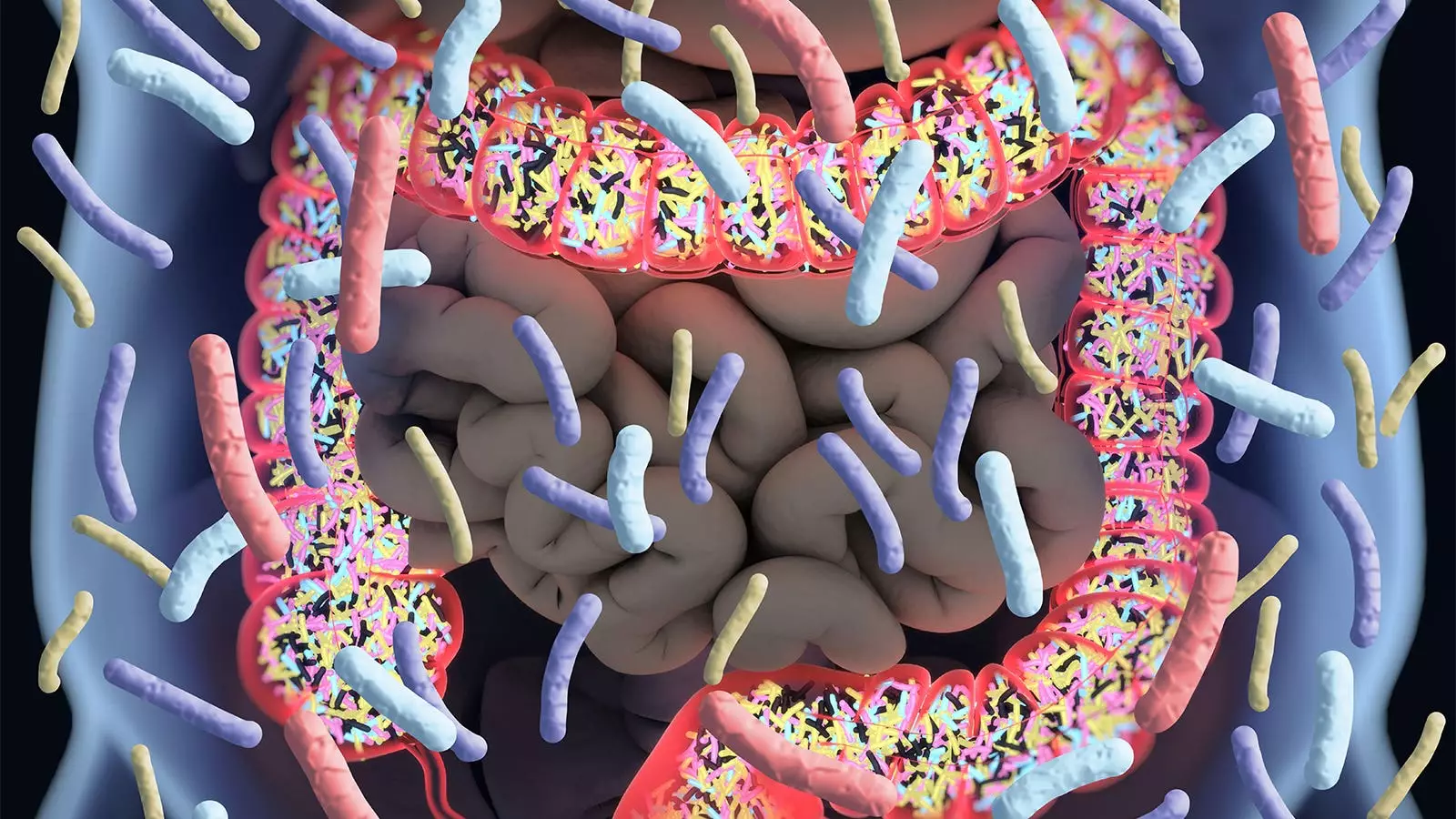

Moreover, an early randomized trial indicated that daily antibiotics could potentially mitigate cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s patients, but subsequent investigations have called this into question, emphasizing the complexity of the issue. These competing results reflect the multifaceted nature of the gut microbiome’s role—a factor that has recently gained attention in neuroscience research, whereby alterations in gut flora due to antibiotic consumption might influence neurological health.

For clinicians, the implications of these findings seem twofold. On the one hand, the results may inspire confidence when prescribing antibiotics to older adults, suggesting that such interventions do not inherently elevate the risk for dementia. The research provides a beneficial context for balancing the necessity of treating infections against the apprehension of potential cognitive repercussions.

On the other hand, healthcare providers must remain vigilant in their interpretations and applications of these findings. The study’s exclusions and population characteristics warrant a cautious approach before generalizing the results to all older patients, particularly those with existing cognitive concerns or complex health profiles.

While this major study offers reassuring evidence that antibiotic use does not correlate with dementia risk among healthy older adults, it also underscores the need for continued investigation into the relationship between antibiotics and cognitive health. Observational studies incorporating diverse populations—especially those with comorbidities—will be crucial for rendering definitive conclusions. Future research efforts should also focus on the impact of antibiotic types and their potential effects on the microbiome to further illuminate our understanding of how best to manage the health of an aging population. As the dialogue between cognitive health and antibiotic usage evolves, it will remain critical for researchers, clinicians, and policymakers to collaborate, ensuring that older adults receive safe and effective healthcare interventions tailored to their unique needs.

Leave a Reply