In emergencies where a person’s heart suddenly stops functioning, every second counts. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) can be the difference between life and death, ensuring that blood continues to circulate and oxygen reaches the brain and vital organs until professional medical help arrives. However, an alarming trend has surfaced in various studies, indicating a disturbing disparity in bystander response: individuals are less likely to administer CPR to women than to men. This gap raises urgent questions about the impact of training materials and societal perceptions on the willingness to intervene in life-threatening situations.

A significant Australian study conducted between 2017 and 2019 analyzed over 4,000 cardiac arrest incidents. The findings were striking: while 74% of men received bystander CPR, only 65% of women did. This disparity suggests not just a bias in the approach of bystanders but also reflects deeper cultural attitudes that might deter individuals from acting in female cardiac arrest cases. The implications are dire, as women experiencing cardiac events may be less likely to survive, often facing worse health outcomes compared to their male counterparts.

Research suggests that societal attitudes, including fears of sexual harassment or misinterpretation of intentions, might hinder bystanders from taking action when a woman is in need of help. Furthermore, the discomfort associated with touching a woman in a critical situation, combined with the perception of women as more delicate, may contribute to reluctance in providing CPR. The difference is stark: women are not only less likely to receive CPR but also less likely to be defibrillated, despite clear protocols to follow.

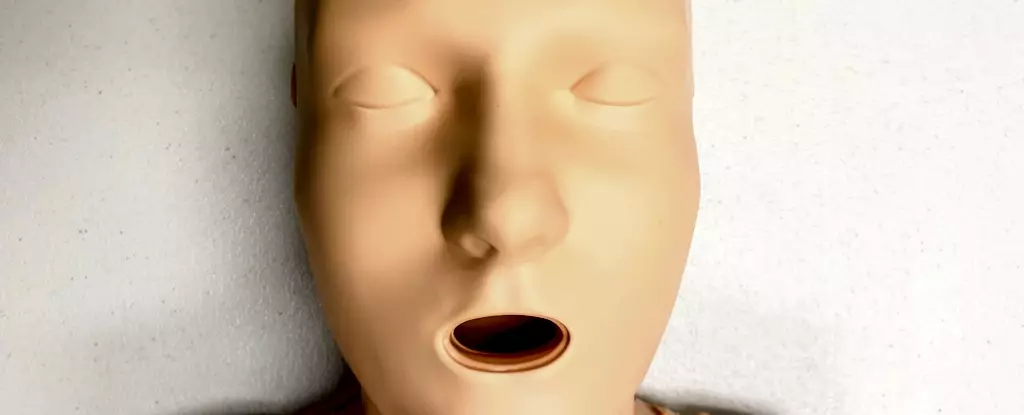

The role of CPR training manikins—commonly used tools in teaching lifesaving techniques—cannot be overstated. However, a startling discovery revealed that 95% of available CPR manikins are flat-chested. This stark representation can perpetuate the mindset that CPR is predominantly a male action, consequently influencing bystander responses in real-life scenarios. The lack of diversity in training manikins, especially concerning female anatomy, suggests that the representation issue must be urgently addressed if we want to improve bystander intervention rates.

Research conducted in the Americas found that most training manikins were not only overwhelmingly male but also predominantly white and lean. Only a small fraction of available manikins represented women, and only one had breasts, which raises critical questions about inclusivity in lifesaving training. The psychological impact of training on real-world actions has been well-documented. If training scenarios lack diversity and fail to depict women accurately, this contributes to hesitance when bystanders encounter real-life emergencies.

Fortunately, it is possible to bridge the observed chasm in gender-sensitive CPR training. By incorporating manikins with various body types, including those with breasts, CPR training can foster a more inclusive environment that reflects the diverse nature of the human population. Furthermore, such changes could empower individuals to feel more comfortable and confident in performing CPR on anyone, regardless of gender.

Understanding the critical signs of a cardiac arrest—such as a person not breathing or lack of responsiveness—should be universally emphasized in training programs for all participants. Bystanders should be equipped with the knowledge that immediate action is vital and that hesitation, influenced by discomfort or misrepresentation, may cost lives.

In situations where defibrillation is necessary, it’s crucial to clarify that removing a bra is not a prerequisite for performing CPR. However, if the need arises, understanding the potential hazards of underwired bras is important for effective defibrillation. This awareness can eliminate additional barriers that might impede timely medical intervention.

The Call to Action

Ultimately, the need for reform in CPR training is clear. Expanding the diversity of CPR training manikins and actively working to raise awareness about cardiovascular health risks for women and marginalized groups are imperative next steps. We must also ensure adequate educational programs that focus specifically on the differences in how men and women experience heart disease, and the implications these differences have for bystander intervention.

As society continues to battle these systemic disparities, it becomes clear that CPR training needs to evolve, making it more inclusive and reflective of the populations it serves. Only by addressing these issues can we hope to improve survival rates and ensure that, regardless of gender, every individual receives the heart-saving assistance they deserve in their time of need. We cannot afford to let societal biases dictate whether someone lives or dies; thus, the movement toward comprehensive, inclusive CPR training is not just important—it’s vital.

Leave a Reply